The UK has long been grappling with a housing crisis that shows no signs of abating. From a shortage of homes to increasing property prices and sustainability concerns, this article explores the details of the crisis and questions how architecture can play a pivotal role in alleviating the challenges. By embracing ethical and sustainable construction practices, reusing existing structures, and implementing effective legislation, we can bridge the gap between housing demand and supply while minimising the environmental impact

Anyone who has picked up a newspaper or turned on the news in the past 20 years will be familiar with the idea of the UK housing crisis but many may not fully understand it or indeed wonder whether the liberal application of the term ‘crisis’ to seemingly every area of life is simply part of party-political hyperbole. So what is the housing crisis, why is it such a problem and what are we going to do about it? Here we aim to answer some of those questions and explain how architecture can provide the solutions.

Fundamentally the housing crisis refers to a failure of the number of homes available to meet the demand. The ever increasing demand is being driven, broadly, by two factors: population growth and changing lifestyles.

The UK population has grown by almost 10million people since the millennium and is predicted to continue growing steadily, reaching well over 70million by the 2040s(1). The population growth is partly down to births outstripping deaths and partly down to net immigration (roughly 60-80% depending on how you calculate it(2). With the average household at 2.4 people(3), we need to have built 4million houses since 2000 (200,000 per year) simply to keep up with the growing population. And population is not the whole picture – lifestyle and social factors like longer life expectancy, delayed marriage and higher divorce rates have all further exacerbated demand.

The rate of house building in the UK has quite simply not kept up with the growth in population: in the last 20 years, the number of new dwellings being built each year has rarely topped 200,00 and has frequently been below 150,000(4).

The disconnect between demand and supply has had serious consequences. First of all it has led to escalating property prices: Since 1988, average house prices have increased by a huge 295% – while this has benefitted homeowners, it has made the dream of homeownership largely unattainable for millions of people. It has also resulted in many families having to be accommodated in temporary accommodation and issues of overcrowding: 3.5% of all households in England are overcrowded (around 829,000 households) (5).

So what is the solution? The obvious answer is to build more new homes. The government target, set out in the 2019 Conservative manifesto, is to be building 300,000 homes a year by the mid-2020s. This target looks very unlikely to be met and is meeting increasingly stiff resistance from politicians and the public alike as the reality of this level of construction is realised. Local people are quite understandably resistant to building on green-belts, new towns in the countryside and ever-expanding suburbs.

Not only is new development unpopular with many but there is another crucial problem with the government target: it would blow the entirety of the UK’s carbon budget to stay within a 1.5deg scenario(6). In other words, the housing target is completely at odds with the net zero target.

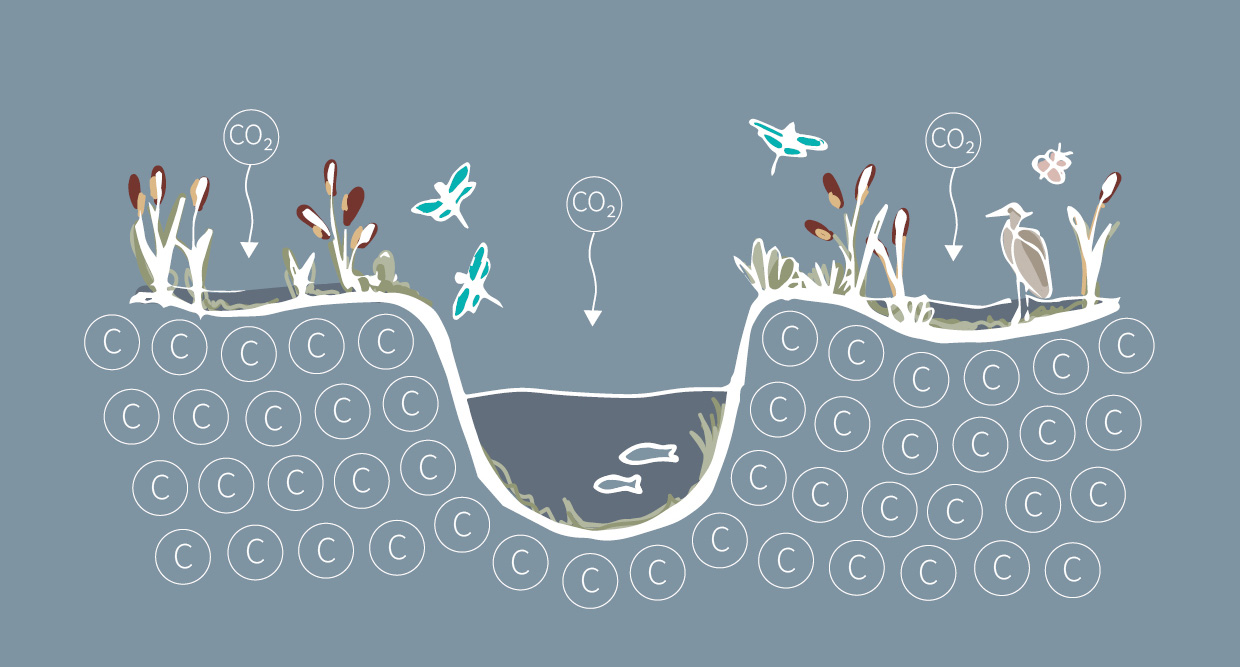

Part of the solution to this is to build new but build low-carbon. We need to completely change the way house-building operates: the conventional cavity walls of brick and concrete block, sitting on concrete slabs and foundations are high in carbon, with a 2-bedroom house typically having an embodied energy of around 80,000kgCO2e (7). The building design has an impact too – mid-rise terraces are far more efficient than detached dwellings or high-rise apartment buildings. By building sustainably, using low-carbon materials such as timber, we could slash up to 60% of the carbon load.

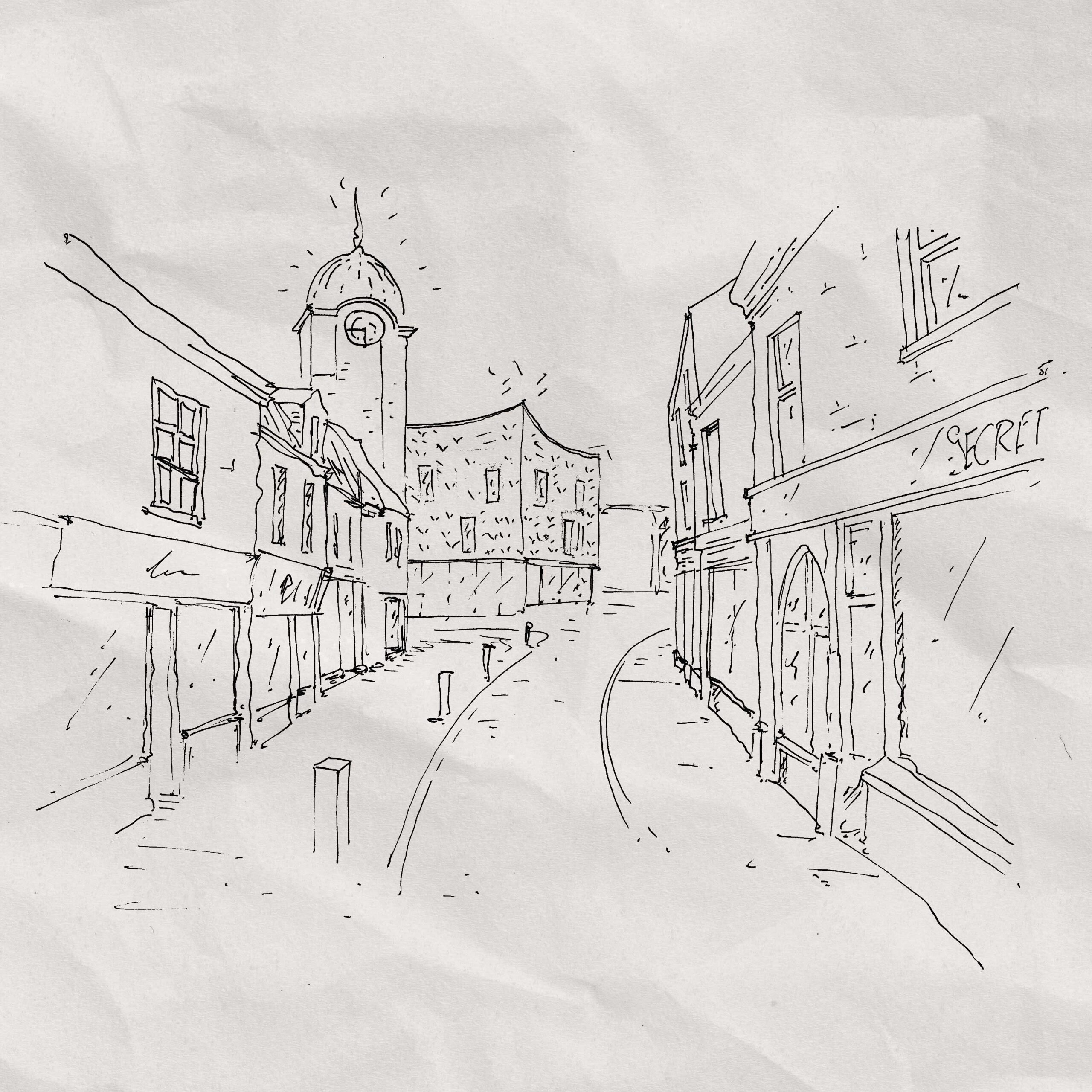

Another solution is to re-think the assets we already have. Existing buildings were often over-engineered and can have additional storeys built on top at a fraction of the carbon-tag. Changes in retail and working patterns are meaning large numbers of town and city centre commercial buildings are becoming redundant or under-utilised. While not always straightforward, creative thinking can find ways of converting (not demolishing and rebuilding!) these structures into desirable dwellings and at the same time rejuvenate our urban centres.

There are legislative solutions to this crisis as well as architectural ones. Currently there are at least 250,000 long-term empty homes in England alone(8), a figure that has risen 20% since 2016. In addition to empty homes, there are around 500,000 second homes in the UK(9) many of which are unoccupied most of time. That is a lot of houses sitting empty and a vastly inefficient use of existing buildings. Some under-use is inevitable, but policies could be implemented to ensure more homes are fully occupied.

While the root causes of housing demand are unlikely to disappear any time soon, architecture can provide solutions which increase the supply without costing the earth.

By Jack Spencer Ashworth, Senior Associate

1. Office for National Statistics https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/january2021

2. https://fullfact.org/immigration/population-growth-migration/

3. Office for National Statistics

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/bulletins/familiesandhouseholds/2020

4. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

5. House of Commons Library

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01013/

6. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800922002245

7. How Bad are Bananas?, Tim Berners-Lee

8. Local Authority Council Tax base England 2021, Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

9. English Housing Survey 2018-19 Second Homes