The latest update of the National Planning Policy Frame (NPPF*), includes an enchantingly simple new requirement that local planning policies and planning decisions should ensure that ‘all new streets are tree-lined…and that appropriate measures are in place to secure the long-term maintenance of newly-planted trees’. If only it were that simple!

During lock-down my running routes took me through several late C20th and more recent housing estates in my hometown, Wymondham in Norfolk. The first of these, Harts Farm, was planned (if memory serves me correctly) during the late 1980’s, and built out during the 90’s. Most of it is now more than 20 years old. Like many estates of a similar age, the residents’ individual gardening efforts have hugely softened the streetscape since it was built. This is most noticeable along the main ‘spine-road’ through the estate, where large front gardens and a number of shared drives left plenty of room for trees and hedges to emerge and survive on an ad hoc basis. When it was designed, the development didn’t have any strong landscaping strategy, but at strategic points of the layout some pockets of landscaping were included to be taken on (or ‘adopted’) by the local council. They would thereby be maintained and protected into the future, for the benefit of all residents and visitors. This is the most notable instance:

The hedge and trees on the left sit between a shared drive and the adopted footpath, and are owned and maintained by the residents who share the drive. The trees on the right, however – one in the distance and the group of three closer in, screening a small parking area – are all owned and maintained by South Norfolk Council. I first noticed the group of three and their associated hedge because an adjacent resident is clearly enjoying watching birds using the feeders that adorn one of them.

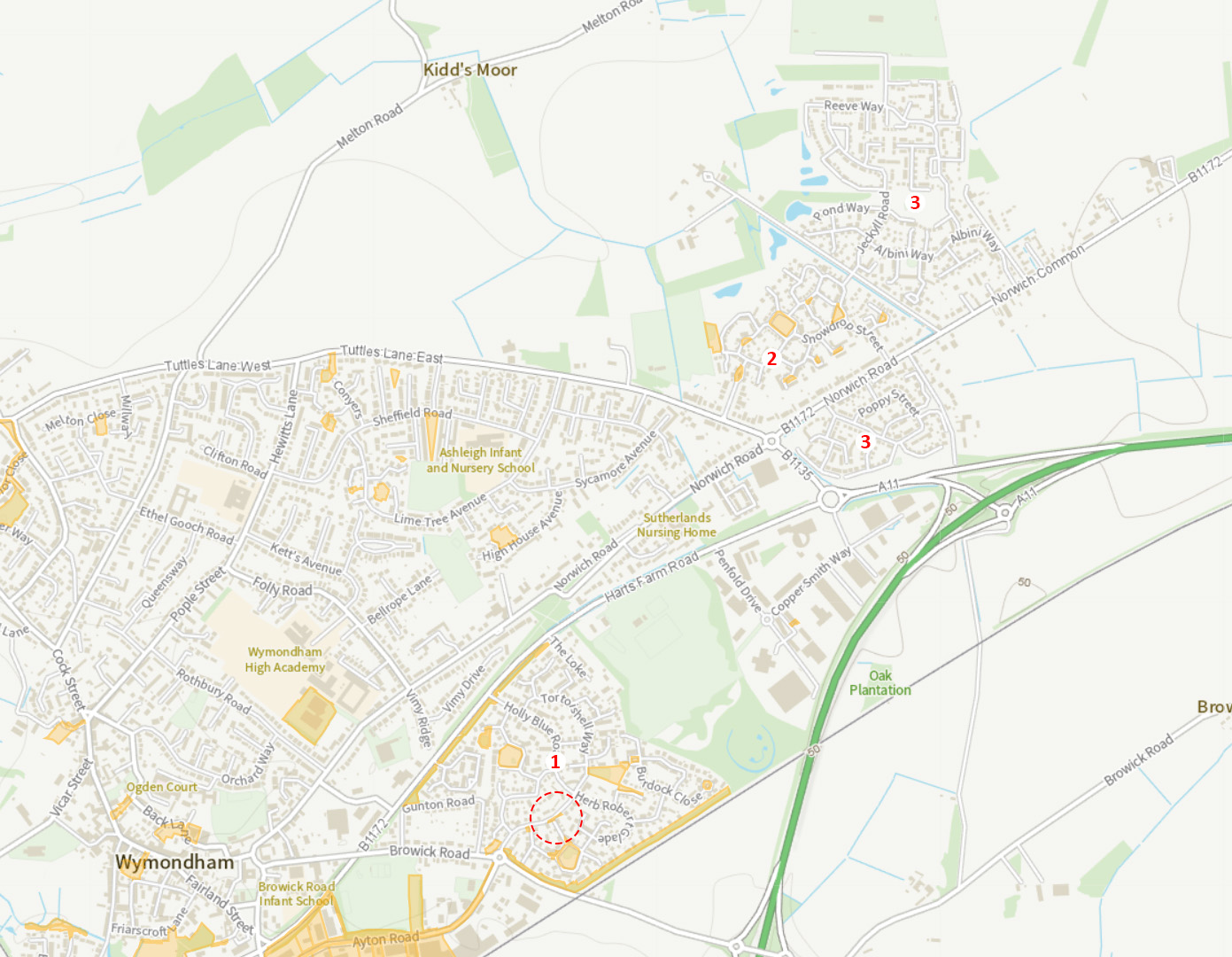

The publicly available online map of South Norfolk’s property assets clearly shows these pockets of landscaping (in orange), each guaranteeing a splash of greenery in the streetscape. There are a few in Harts Farm (labelled 1, with these trees ringed) and even more in Whispering Oaks (2). This estate was planned a decade later that Harts Farm, under a push for improved street-scape design demanded by central government’s Planning Policy Guidance Note 3 (PPG3).**

You may notice that more recent developments nearby (3) have no similar areas of adopted landscaping. In an era of shrinking local authority budgets South Norfolk will no longer adopt small areas of street-scene landscaping. Instead, the long-term maintenance and protection of street trees is left in the hands of the housebuilders and whatever private management-company arrangements they set up for each development. It might be argued that this is the right direction of travel. Why should a local taxpayer contribute to the provision and up-keep of trees that will benefit residents of an estate they may never visit? And it is certainly the case that on smaller developments, residents’ management companies can be a very effective way to maintain shared private drives and areas of associated landscaping. But the recent controversy over alleged abuse of leasehold tenure by some large housebuilders has made the whole subject of ground rents and management charges very contentious. In this context, the trajectory towards less and less shared landscaping would look set to continue, unless the new NPPF ‘tree clause’ has the desired effect.

The new NPPF is heavily influenced by the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, set up by the government in 2018. The Commission has a penchant for traditional architecture, and this push for ‘tree-lined streets’ is no doubt inspired by the Georgian ‘great estates’ of London, Bath and Edinburgh. These fashionable up-market residential districts all used leasehold tenure to allow the landowners to ‘stay in’ and benefit from the long-term value growth of their real estate. In this context, street trees and gated squares were seen as value-drivers to be nurtured and protected, not construction costs to be avoided or off-loaded as quickly as possible. Similar thinking under-pinned the Garden City movement, producing the gloriously simple streetscapes of Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City. Even Milton Keynes, long derided for its roundabouts and concrete cows, is a new town with tree-lined streets built into its DNA.

What Bloomsbury, Welwyn and Milton Keynes have in common is a mechanism for buying and maintaining street-trees based on capturing a slice of the land value uplift that building a new residential district creates, and a financial model where the developer stays invested in the place for the long term. It will be interesting to see how developers and planners embrace their new instruction to create tree-lined streets within the current ‘build it/sell it/move on’ model of UK PLC housebuilding.

*The NPPF is the over-arching set of central government policies with which the local plans of each local authority must comply.

** One of a bookcase-full of planning policy guidance notes replaced by the first edition of the NPPF

Gloriously simple landscaping – trees, hedges, grass – at Welwyn Garden City.

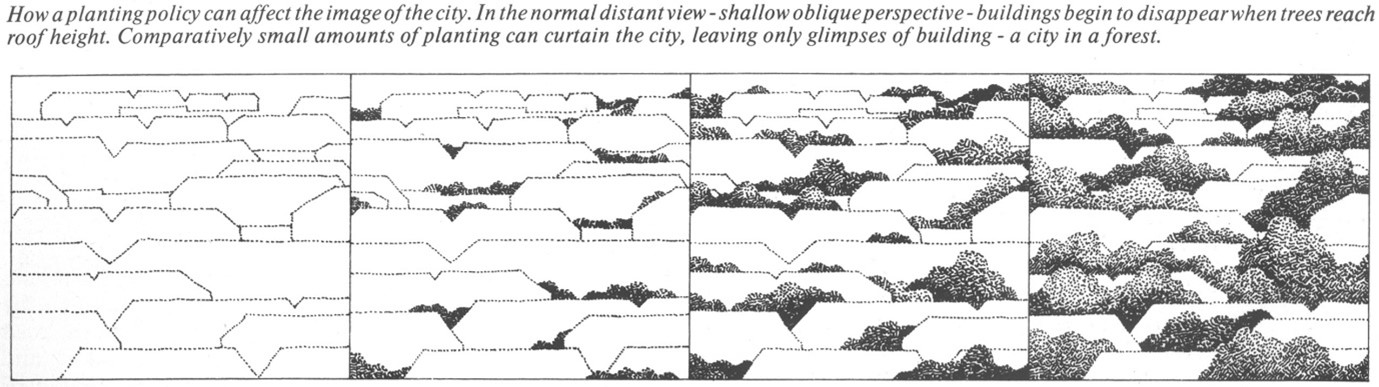

‘Milton Keynes – Forest City?’ from ‘The Architecture & Planning of Milton Keynes’ by Derek Walker.

Milton Keynes – forest city!

Matt Wood, Head of Housing

October 2021