Despite the unseasonably warm Autumn, the successive hikes to energy prices begin to hurt as we turn on our heating systems for the winter. Sadly, these prices are unlikely to abate over the coming years. The National Grid requires significant expansion to cope with the transition of fossil fuel industries for heating and transportation over to electric power sources (such as Electric Vehicles and Heat Pumps). Two new nuclear power stations are under construction, but this does not even cover the five scheduled for decommission later this decade.

Solutions for cheap renewable energies are established (solar, wind) but these are highly reliant upon weather – and our quirky little island is prone to be sunny and windy at the same time, or dark and still. We need a network of batteries to store and release this cheap renewable energy when the grid needs it. Technologies are emerging (gravitational, chemical, thermal, mechanical), but these need significant investment to rapidly scale up.

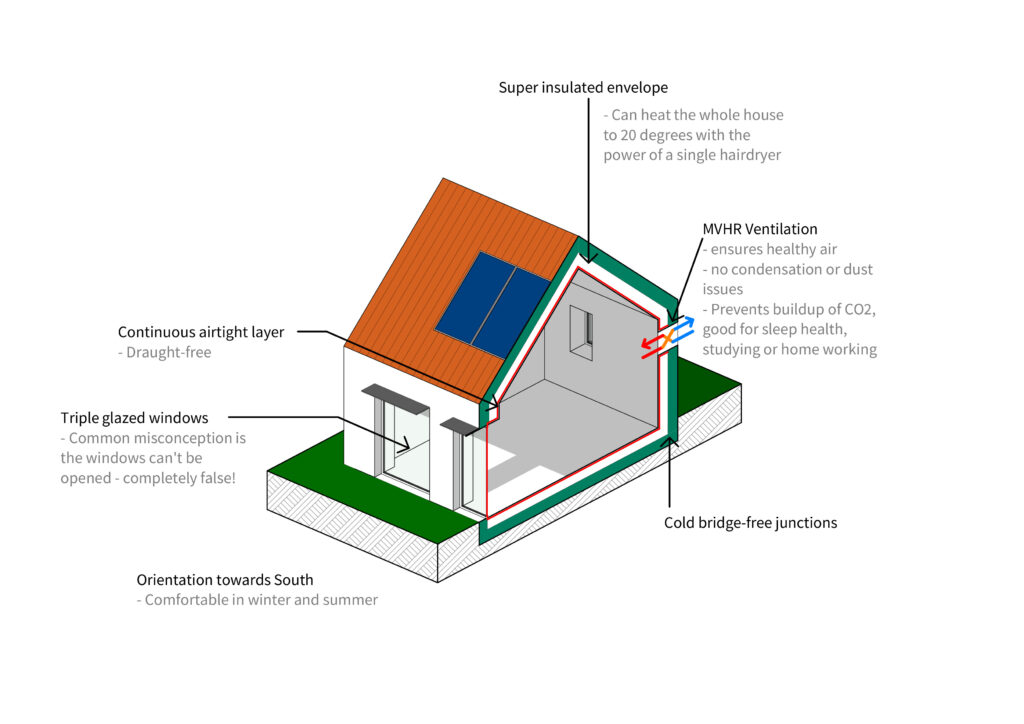

As Jack said in our earlier post, the cheapest unit of energy is the one not used. For new houses, we fortunately have the knowledge on how to reduce energy loss, through a fabric first approach. Orientation, form, and high levels of insulation can all work together to build a house that is incredibly resilient to the coldest winters (only requiring the energy of a single hairdryer to comfortably heat the whole house), but also in summer.

It’s an inescapable truth our climate is going to be more turbulent over the next century, and whilst we have the solutions for new houses, we really must address the 27million homes that already exist in this country, which is a much more difficult challenge. Throwing solar panels and air source heat pumps may help, but these require maintenance and have a limited lifespan. Insulating the building fabric, a fabric first approach, will last the lifespan of the building.

Retrofit projects can be phased but is important that the implication of each measure is fully understood, that only doing half the job doesn’t lead to negative consequences – for instance, draughtproofing without additional ventilation can lead to a build up of stale air and condensation.

Secondly, before embarking upon retrofit works, an understanding of the condition of the property is vital – there is very little point in insulating between floor joists which are in bad condition and will only need to be removed in a few years’ time. Conversely, these maintenance tasks when workmen are already onboard are the perfect opportunity to consider insulating the building fabric.

Of those 27 million existing houses, as well as being made from a whole host of different materials, there are several different forms to consider. With each of these styles of properties, there are some ‘easy-wins’ – retrofit measures which are simple and relatively inexpensive (such as insulating loft spaces, reducing heat loss in a house by as much as 25%). Some measures are still worthwhile but are more disruptive and expensive.

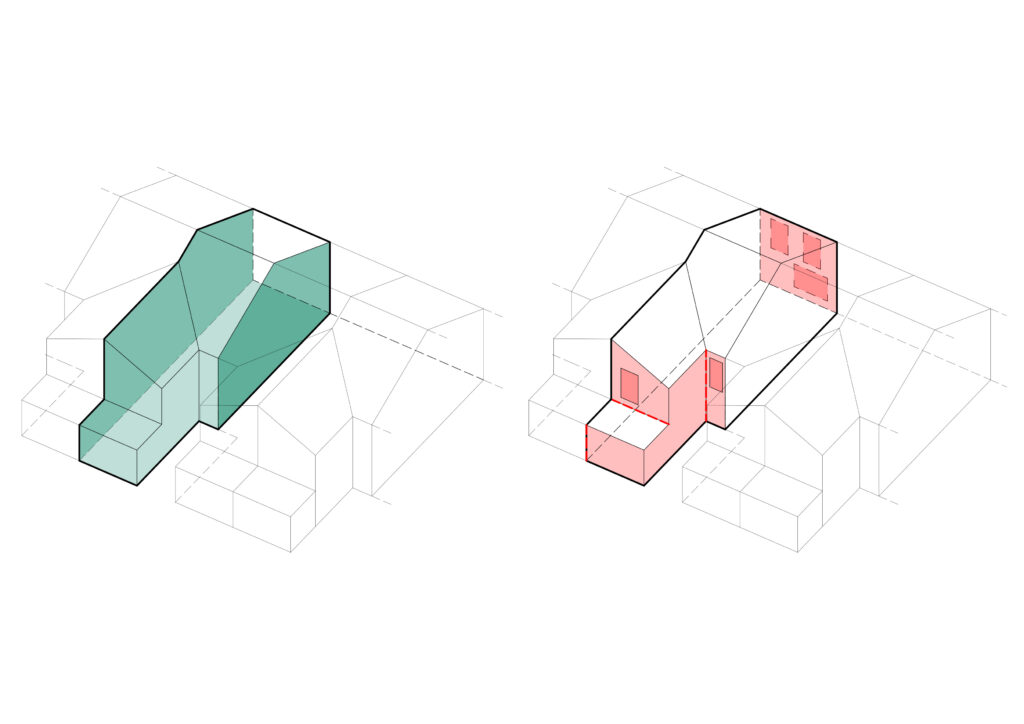

Terraces have an early advantage in that there are shared walls with neighbours on both sides, and far less surface area of wall to upgrade. However, complications lie on how best to insulate the sections of external wall that are present. Terraced streets often lie within conservation areas and may preclude external wall insulation (EWI), which has aesthetic implications but is better at eliminating thermal bridges. Furthermore many of these terraces still retain sash windows, and whilst triple-glazed replacements that match their historic counterparts in appearance can be found, they do tend to be expensive

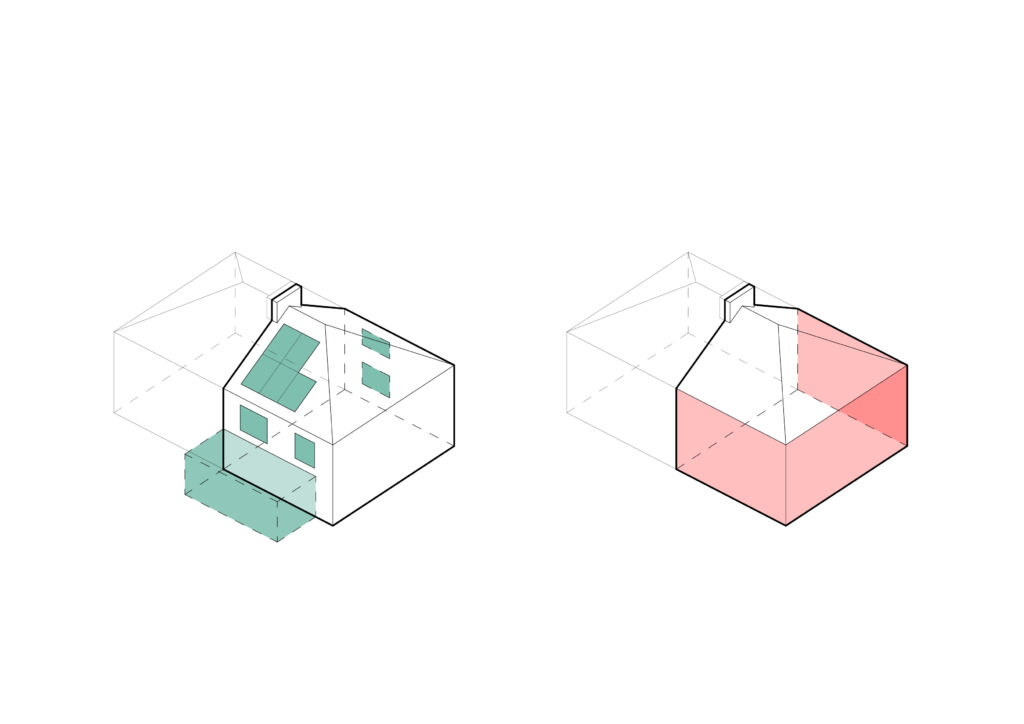

Slightly larger houses, such as semi-detached or detached barns, have a different set of easy-wins and challenges. These houses tend to have simple, large roofs which provide ample space for a solar array. Furthermore, the additional garden space around offers opportunities to extend with high-performance walls. The downsides are that there is substantially more wall to insulate, and often have a concrete floor that is disruptive to replace.

Listed Buildings are far more challenging. Whilst there is an allowance in Building Regulations to not upgrade the building fabric to the higher standards expected in other buildings, this leaves Listed Buildings with considerably higher operational expenditure which is unsustainable in the long term. Whilst we need to protect and conserve buildings of significance there needs to be greater discussion between designers and Local Authorities on how to do this with a sense of pragmatism. To that end, some Local Authorities (such as Kensington and Chelsea) have removed the need for listed building consent to install solar panels, providing certain criteria is met.

Watch out for the third part in our retrofit series for more on how legislative changes are needed to support and encourage more retrofit!

By Sam Steel, Architectural Assistant