Embodied carbon is a vitally important part of the overall carbon footprint of any building and it is becoming increasingly significant.

For decades now, sustainably minded clients have sought to commission low-energy buildings, sometimes called ‘eco homes’. The focus for these buildings was operational energy – primarily the energy used to heat the building, although other operational energy use such as hot water heating, ventilation, lighting and water use were also targeted. These well insulated buildings use much lower amounts of fossil fuels to heat them and were therefore considered sustainable. The gold standard for this approach being buildings built to Passivhaus principles which are so efficient they require little to no heating system at all.

In recent years however it has become obvious that, while operational energy is vitally important in driving down the carbon footprint of our buildings, it misses a significant chunk of the problem: embodied carbon. What on earth is embodied carbon I hear you say? Well, embodied carbon is the carbon footprint of the building itself – the carbon emissions associated with the production of the materials, their transport to site, construction, maintenance and eventual demolition and disposal. There is no point in building an ultra low energy passive house if it is cast entirely from concrete – the client’s bills will be very low but the impact on the planet will be enormously high.

Embodied carbon is a vitally important part of the overall carbon footprint of any building and it is becoming increasingly significant. Why? The reasons for this are twofold: firstly, buildings are becoming more and more insulated meaning the operational energy as a proportion of the whole is reducing; secondly, the national grid is decarbonising fast which means the carbon intensity of the energy used is also lower. Embodied carbon can now represent around 30% of a standard building’s footprint and as much as 75% for an ultra-low energy building.

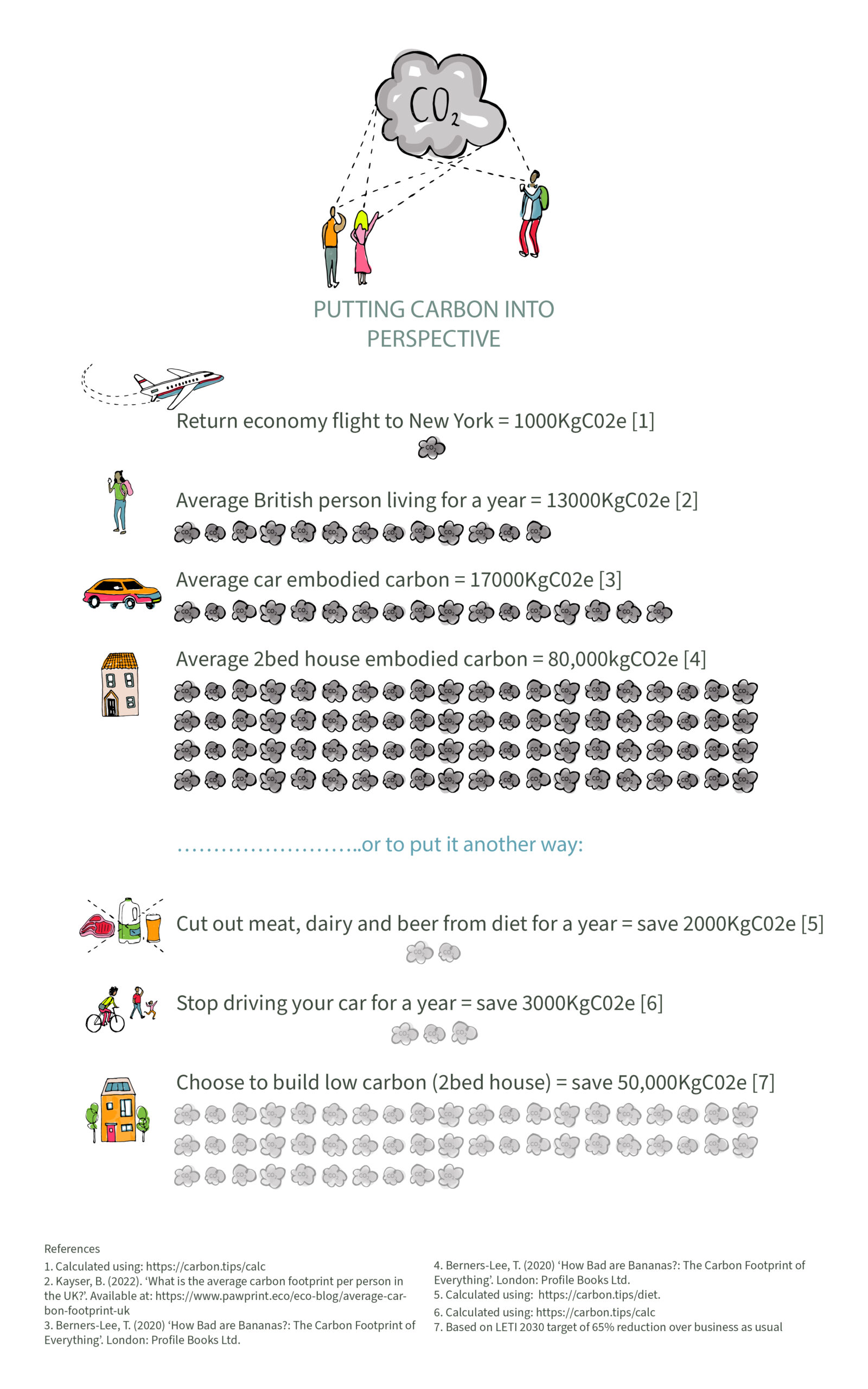

The numbers are terrifyingly large. The embodied carbon of an average 2 bedroom house is in the region of 80,000kg of C02e (carbon dioxide equivalent). That’s the same as 80 return flights to New York or a family of 6 living for a year! It is therefore not so surprising that the construction industry is responsible for almost half of all carbon emissions in the UK.

Given the scale of the problem, and the fact that the UK government has committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050, you might think there would be some kind of regulation to reduce embodied carbon in construction. Extraordinarily, there are no mandatory targets for embodied carbon whatsoever as yet. That may eventually change with the proposed ‘Part Z’ amendment to the building regulations being pushed forwards by Norfolk MPs, initially Duncan Baker (North Norfolk) and now Jerome Mayhew (Broadland). Within the last few days, The Environmental Audit Committee has published its findings from the inquiry into the sustainability of the built environment (‘Building to net zero: costing carbon in construction’) and made some very clear recommendations to the government, including the phasing in of whole life (embodied + operational) carbon assessments, and eventually targets.

While the government catches up, the rest of us are trying to deal with a climate emergency. Many within the industry are painfully conscious of the moral obligation to address these issues. Targets for embodied energy (as well as operational energy and water use) have been set by industry bodies such as LETI and the RIBA. Willing businesses, such as ourselves, have voluntarily signed up to meeting these targets and are now tackling the problem head on. Make no mistake, this is a huge challenge: we must now build in entirely new ways and at the same time we must learn how to measure embodied carbon and use these tools to feedback into the design process.

The good news is that it can be done and frequently savings in embodied carbon go hand in hand with cost savings. Huge savings in embodied carbon can be made by building less (e.g. reusing existing structures), building efficiently and re-using old materials. New materials that are required can be specified as low carbon: in general this means moving away from carbon heavy materials like concrete, steel, aluminium and brick and moving towards locally sourced, bio-based and natural materials such as timber and lime. As much as 50,000KgC02e (around 60%) of the embodied carbon of that 2 bedroom house can be eliminated with low carbon design.

At Hudson Architects, we believe that a building design can no longer be classed as a good design unless it is sustainable. We will continue to drive down the embodied carbon of our buildings, whether the government asks us to or not!

Written by Jack Spencer Ashworth, Head of Sustainability.